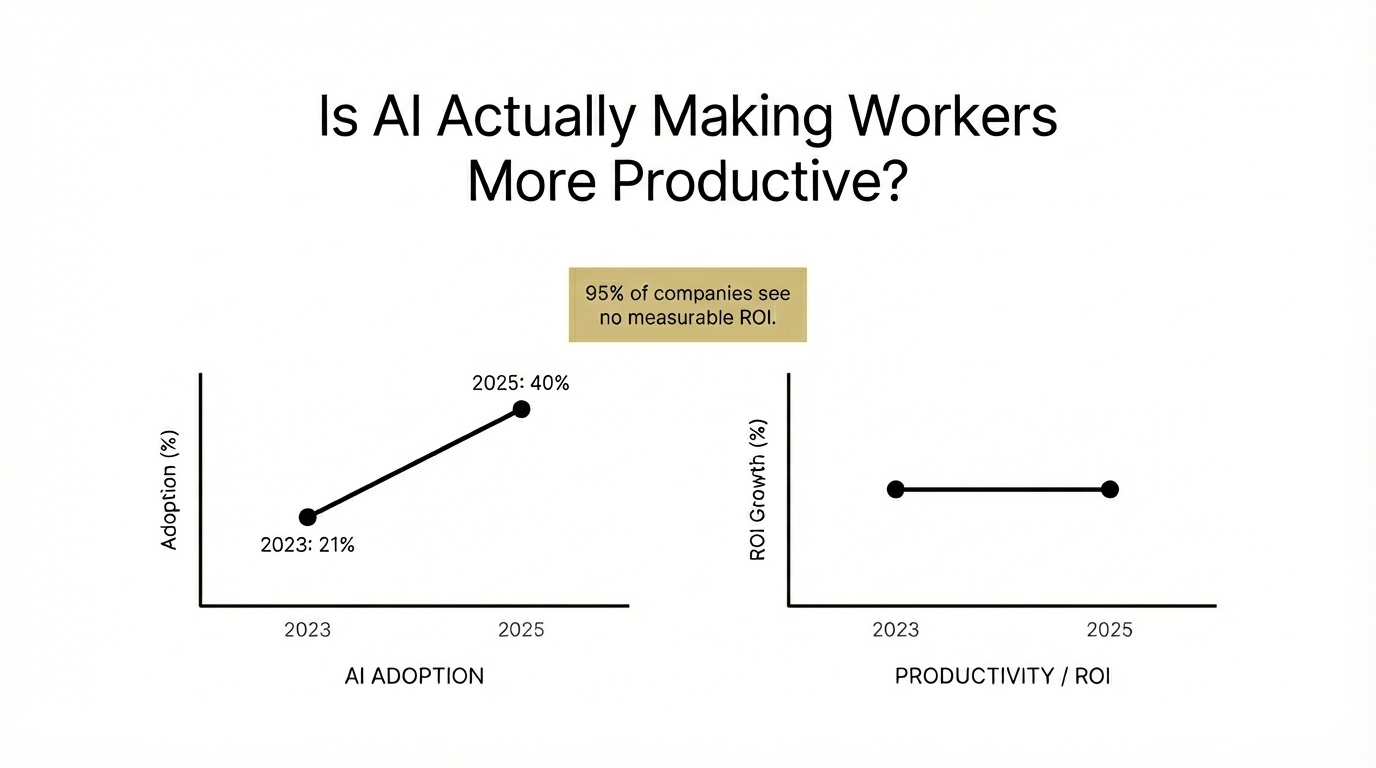

The numbers tell a contradictory story. Artificial intelligence adoption in the workplace has doubled since 2023, climbing from 21 percent to 40 percent of workers using the technology regularly. Companies have poured billions into generative AI tools, and executives speak of transformation in nearly every earnings call. Yet according to a recent MIT Media Lab report, 95 percent of organizations see no measurable return on their investment.

This gap between enthusiasm and evidence has become one of the defining puzzles of the current AI era. Workers are using the tools. Companies are buying the licenses. But the productivity revolution that was supposed to follow has, for most organizations, failed to materialize.

The explanation, according to a growing body of research, is more complicated than early adopters anticipated. AI's productivity benefits are real, but they are also highly conditional, dependent on who uses the tools, how they are deployed, and whether organizations have done the unglamorous work of fixing the processes AI is supposed to enhance.

The Productivity Paradox Takes a New Form

Economists have a term for this phenomenon. The Solow paradox, named for Nobel laureate Robert Solow, describes the puzzling disconnect between rapid advances in information technology and sluggish growth in measured productivity. In 1987, Solow quipped that you could see the computer age everywhere except in the productivity statistics. Nearly four decades later, the same observation applies to artificial intelligence.

A 2025 meta-analysis published in the California Management Review pooled 371 estimates from studies conducted between 2019 and 2024. The researchers found no robust relationship between AI adoption and aggregate labor-market outcomes once they controlled for methodological differences across studies. Results varied dramatically depending on how researchers defined AI, which sectors they examined, and whether they adjusted for other factors like capital investment.

This does not mean AI lacks value. Rather, it suggests that the pathway from individual task acceleration to organizational productivity is longer and more treacherous than vendor case studies imply.

The implicit logic underlying most AI adoption is straightforward: if AI can speed up individual tasks, organizational productivity will naturally follow. But this assumption breaks down in practice for reasons that are only now becoming clear.

When AI Creates More Work Than It Saves

One of the most striking findings to emerge from recent research involves a phenomenon that Stanford professor Jeff Hancock and BetterUp Labs vice president Kate Niederhoffer have termed "workslop."

The concept emerged from a familiar experience. Hancock noticed something peculiar in the research assignments he was grading in late 2022, shortly after ChatGPT's public release. The papers looked polished on the surface but lacked substance. And because he had a hundred students, he could see that multiple assignments shared the same hollow quality, verbose, well-formatted, and ultimately empty.

Niederhoffer encountered the same pattern in professional settings. She received a speaking request that summarized her research in ways that revealed the sender did not actually understand her work. Reading it felt strangely effortful, even for someone accustomed to processing large volumes of information quickly.

They now define workslop as AI-generated work content that masquerades as good work but lacks the substance to meaningfully advance a given task. According to their survey of 1,150 full-time U.S. workers, 40 percent report having received workslop in the last month. Those who encounter it estimate that roughly 15 percent of the content they receive at work qualifies.

The problem is not merely aesthetic. Workslop shifts cognitive burden downstream. When someone uses AI to generate a polished-looking document without doing the underlying thinking, the recipient must decode the content, infer missing context, and often redo the work entirely. The time saved by the sender becomes time lost by the receiver.

Survey respondents reported spending an average of one hour and 56 minutes dealing with each instance of workslop. Based on participants' self-reported salaries, the researchers calculated an invisible tax of $186 per employee per month. For an organization of 10,000 workers, given the estimated prevalence of workslop, this yields over $9 million per year in lost productivity.

The phenomenon occurs across hierarchies. Most workslop flows between peers, but 18 percent travels upward from direct reports to managers, and 16 percent flows downward from managers to their teams. Professional services and technology sectors are disproportionately affected.

The Collaboration Myth

Beyond workslop, research has challenged another foundational assumption about AI deployment: that human-AI teams inevitably outperform either working alone.

A comprehensive meta-analysis published in Nature Human Behaviour examined 106 experiments on human-AI collaboration. The finding was counterintuitive. On average, human-AI combinations performed worse than the better of the two working independently. The cyborg advantage, combining machine speed with human intuition, did not materialize in most contexts.

Performance improvements emerged only in specific circumstances, particularly open-ended creative tasks like brainstorming. Decision-making and judgment tasks, by contrast, suffered from over-reliance on AI suggestions and confusion over authority and responsibility.

This pattern has important implications for how organizations deploy AI. Rather than defaulting to hybrid approaches across all functions, managers must map tasks along what researchers call a creation-versus-evaluation matrix. AI excels at generating first drafts and divergent ideas. High-stakes approvals and risk assessments should remain with whichever agent, human or algorithmic, demonstrably outperforms in that specific domain.

The Skill Gradient

If AI's benefits are conditional, one of the most important conditions is the skill level of the person using it.

A July 2025 systematic review examined 37 studies of large-language-model assistants for software development. While developers spent less time on boilerplate code generation and API searches, code-quality regressions and subsequent rework frequently offset the headline gains. The pattern was especially pronounced as tasks grew more complex. Senior engineers found themselves investing substantial time checking AI output for subtle logic errors that junior developers might have missed entirely.

Similar findings emerged from a randomized controlled trial involving more than 5,000 agents at a U.S. tech support desk. AI assistance delivered a 35 percent throughput lift for bottom-quartile representatives but almost no gain for veterans who had already optimized their workflows.

This skill gradient creates a paradox for organizations. AI tools may help struggling performers catch up, but they do little for top performers, and may actually slow them down by introducing verification overhead. A 2025 meta-analysis of 83 diagnostic-AI studies found that generative models now match non-expert clinicians in accuracy but still trail experts by a statistically significant margin.

The implication is that AI deployment strategies must differentiate by user type. Junior employees and lateral hires may benefit from always-on copilots. Experts derive greater value from fine-tuning capabilities or plugin integrations they can control directly.

The Gray Work Problem

Even when AI tools function as intended, their benefits can be neutralized by the environment in which they operate.

The 2025 Gray Work Report from Quickbase documents a troubling pattern: 80 percent of businesses increased investment in technology over the past year, yet 59 percent of workers say it feels harder than ever to be productive. The report describes employees drowning in a sea of applications, spending more than 11 hours per week simply chasing down information across disconnected systems.

This phenomenon, which the report terms gray work, refers to the manual labor required to connect siloed tools and fragmented data. Workers spend hours copying information between platforms, reconciling conflicting records, and performing tasks that should be automated but are not because systems do not communicate with one another.

AI cannot fix a workplace where the underlying data architecture is broken. If a generative AI tool operates in one system but cannot access data from another, workers still must perform the gray work of connecting the dots manually. The technology becomes another layer in an already overwhelming stack rather than a genuine productivity unlock.

The report found that while 85 percent of workers now trust AI to improve how work gets done, up from 59 percent in 2024, 89 percent still harbor major concerns about data security and compliance. And 52 percent of respondents use AI tools daily, more than double the share from the prior year. But these tools are being deployed on top of fractured processes that limit their effectiveness.

The Stress Paradox

One of the original promises of workplace AI was reduced stress. Automating routine tasks would free mental energy for more meaningful work, the theory went. Employees could escape drudgery and focus on creative and strategic activities.

The evidence suggests otherwise. Research has found substantial correlations between technology overload and job insecurity fears, both of which contribute to psychological strain and performance declines. Generative AI chatbots and auto-reply systems create new sources of stress rather than eliminating existing ones: constant notifications, unclear responsibility for AI-generated content, and the mental burden of managing AI interactions.

Organizations that deploy AI without examining mental load alongside workload risk trading one form of burnout for another. Rotating responsibilities so that no employee spends entire days wrestling with AI prompts, enforcing communication boundaries, and pairing AI rollouts with explicit recovery periods can help mitigate these effects.

What Separates Success from Failure

Despite these challenges, some organizations are capturing genuine value from AI investments. The difference lies in deployment strategy rather than the tools themselves.

The California Management Review analysis identifies several characteristics of successful implementations. Organizations that see returns begin with evidence audits, benchmarking performance using metrics that match specific tasks: code-review defects for development teams, customer satisfaction scores for service functions, error rates for analytical work. This baseline measurement enables accurate assessment of AI's actual impact rather than reliance on subjective impressions or vendor claims.

Task triage emerges as a critical capability. Managers must systematically evaluate which work should remain fully human, which would benefit from a hybrid approach, and which can become autonomous. Each organization must develop its own mapping based on context and capabilities rather than applying generic frameworks.

Governance structures matter as well. Installing confidence disclosures helps users understand when to override AI suggestions. Well-being guardrails, including mandatory pauses, notification-free zones, and rotation systems for intensive prompt work, help prevent new forms of technostress.

Recruiting firms that specialize in AI-era talent acquisition, such as AI recruiting agency, Edison & Black, have observed that organizations succeeding with AI typically invest as heavily in change management as they do in the technology itself. The tools are only as effective as the processes and people surrounding them.

The Agency Factor

Research from BetterUp Labs has tracked predictors of generative AI adoption since 2023. Workers with a combination of high agency and high optimism, termed pilots rather than passengers, use AI 75 percent more often at work than their counterparts with low agency and low optimism, and 95 percent more often outside of work.

More importantly, pilots use AI differently. They are far more likely to deploy the technology to enhance their own creativity. Passengers, by contrast, tend to use AI to avoid doing work. The distinction helps explain why two employees with access to identical tools can produce vastly different outcomes.

This finding suggests that mindset interventions may be as important as technical training. Organizations that frame AI as an augmentation of human capability rather than a replacement for effort see better results. Teams that spend time discussing how they use AI and critiquing applications for their specific needs develop shared norms that reduce workslop and improve output quality.

Transparency helps as well. When employees disclose that work is AI-assisted, recipients can calibrate their expectations and fill in gaps more effectively. The burden-shifting dynamic that characterizes workslop often stems from opacity about how content was produced.

The Path Forward

The evidence does not support abandoning AI investments. It does, however, demand a more sophisticated approach than most organizations have adopted.

AI's productivity dividend is real in specific contexts, for specific users, and under specific workflow designs. It is not universal, automatic, or guaranteed. The myth of blanket productivity enhancement has given way to a more granular reality in which success depends on thoughtful deployment rather than enthusiastic adoption.

Organizations that treat AI implementation with the same analytical rigor they apply to capital budgeting or safety engineering will outperform those chasing headline gains. This means measuring both leading indicators like time saved and lagging indicators like total factor productivity and quality metrics. It means differentiating deployment strategies by task type and user skill level. And it means fixing the underlying process fragmentation that prevents AI from delivering on its potential.

The question of whether AI is making workers more productive does not have a single answer. For some workers, in some roles, with some tools, under some conditions, the answer is clearly yes. For the majority of organizations investing heavily in the technology, the honest answer remains -- not yet.